The uprising at the Athens Polytechnic University between the 14th and 17th of November of 1973 is forever embedded in contemporary Greek history. But its memory and radical character has undergone tremendous transformations. What started off as a student protest related to student elections quickly became - with the participation of workers, pupils and other non-students - a violent struggle aiming for the complete overthrow of the dictatorship. Behind the calls for peaceful democratic transition, barricades were lit on fire, police stations were burned down and public buildings occupied and ransacked. These were the events that posed a real threat to the dictatorship, leading to the inevitable intervention of the army to suppress the uprising and restore order.

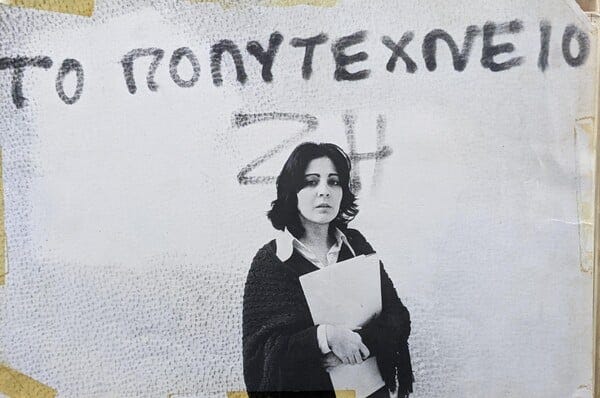

In the first years after the collapse of the junta in 1974, commemorations of the uprising retained a radical, oppositional political character - until the election of Pasok in 1981. In the following years, it became an official, state-sanctioned celebration and its radical character watered down to a national democratic festival with an overwhelming emphasis on the students and a gradual erasure of the activities of radical proletarians. This transformation allowed many of the student protagonists to build political careers and land in positions that contributed to the reversal of the content of the uprising, ‘disciplining’ any attempt to maintain its radical spirit or utilise it as a critique of the post-dictatorship political landscape. In the last decades, and not coincidentally, official commemorations are accompanied by the establishment of a veritable police state.

Starting today, and with a new post everyday until this Sunday, the aim here is to illuminate the radical gestures of this uprising, to ponder on the political debates that were taking place inside the struggle and to bring to light the events that remain intolerable for both contemporary governments and the official left.

November 14th, 1973

Around 13.00 of this mildly cold Wednesday afternoon, around one thousand students had gathered at the stairs of the Athens Law School. There, they engaged in debates and fiery speeches about the first free student elections to be held after 6 years of dictatorship, which had just had been announced by the newly appointed Prime Minister of the dictatorship, Spyros Markezinis.

Markezinis had just replaced the previous head of the junta, Georgios Papadopoulos, tasked with an officially expressed aim of calling for national parliamentary elections. Rather than seeing this as a real opening, however, many saw it as a transparent attempt to legitimise the dictatorship. The experience of a ‘referendum’ that had taken place shortly before, in which the dictatorships’ choice received 92 per cent of the vote, was too fresh.

As the students continued debating at the Athens Law School, a rumour emerged that students at the close-by Polytechnic University had been attacked and beaten by the police. Choosing to respond to this immediately, the first demonstration was formed heading towards the Polytechnic. The organised left would soon call those who organised this first demo the “300 provocateurs”.

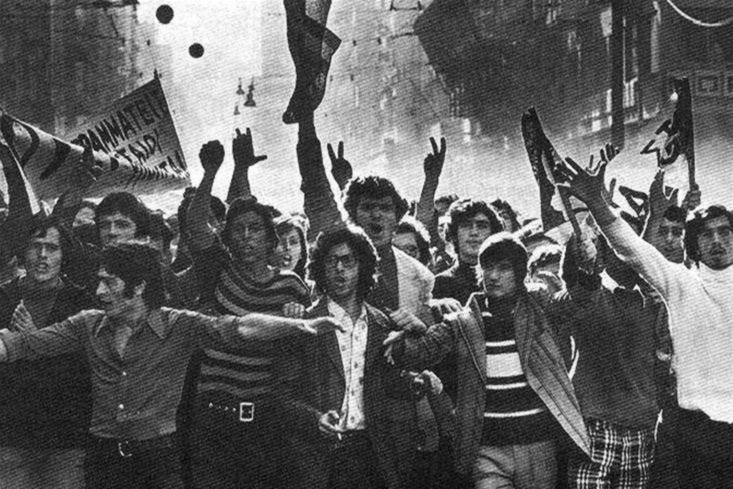

14 November 1973, the first demonstration is formed heading from the Law School towards the Polytechnic.

The rumour of the police intervention turned out to be false. But it didn’t matter any longer. The students arrived at the Polytechnic at the same time as the police who had been alerted, who then proceeded to attack them. To defend themselves, the students went into the Polytechnic and started throwing bitter oranges at the police. Soon, the bitter oranges turned into stones.

Inside the Polytechnic, other students had also been holding assemblies to discuss the student elections. Taken by surprise, they did not want this to escalate. Fierce debates took place but some of those wandering around remembered that in a previous attempt at an occupation, the police had taken advantage of the open doors and stormed the University arresting many. A small group therefore decided to lock the gates to prevent such a surprise attack. Seeing the students perplexed by their inability to use the keys, a 15 year old construction worker took an initiative and used a rebar to secure the gate. Unbeknownst to most students who were still debating in the assemblies and the illegal but organised left forces (1) which was trying to de-escalate the situation, the occupation had become a fact. There was no turning back.

With the gates locked down and increasing numbers of police surrounding the building, no one could leave without fear of arrests. In that moment, the Dean of the Polytechnic together with two students, met with the head of the police and asked for the withdrawal of the police forces - so that those who wanted to leave, could do so safely. After that, the police withdrew to nearby streets opening a temporary exit. Some of those who opposed the occupation or had just found themselves in the Polytechnic unaware of what was happening, decided to take the opportunity and leave. Many of them were criticised and shouted down by the ones who had decided to continue the de facto occupation but it was after exiting the University and seeing large groups of people heading there that many decided to return. Soon after and despite contrary attempts by the organised left, the assembly voted for the continuation of the occupation.

Until that moment, the atmosphere remained joyous and celebratory, if not somewhat reluctant. But as the night was closing in, and more students arrived from other Universities (around 18.00, around 1000 students who had taken the train from Piraeus arrived at the Polytechnic), the climate started to change.

Anarchist slogans: “Down with power”, “Against capital, state and army”

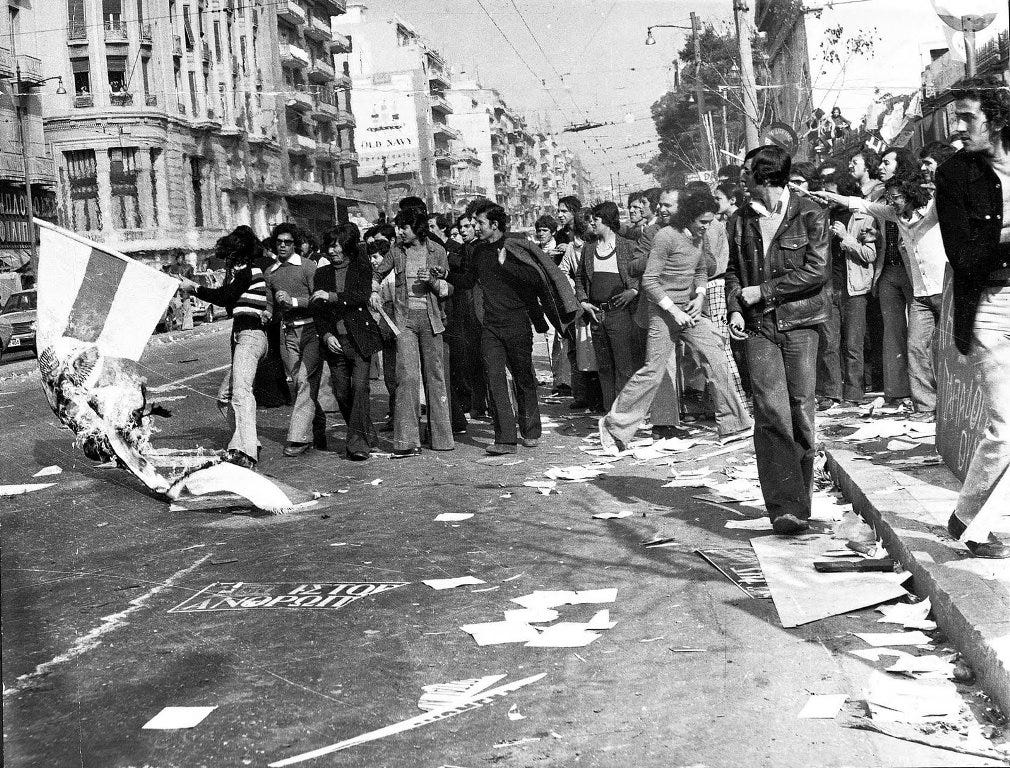

The inability of the organised left to maintain discipline even over its own members and the proliferation of more radical leftist groups and some anarchists pushed in the opposite direction of de-escalation. Seeing this development, the organised left took action, attacking the anarchists (some of whom had already started making Molotovs) and erasing their slogans (see Appendix). Nonetheless, the atmosphere remained seductive and undisciplined throughout the night.

November 15th, 1973

While the uprising is today commemorated as a student rebellion, it was the massive participation of workers that radically changed the climate and created a real challenge for the junta. Those radical elements of the working class had created autonomous networks that were outside the control of both junta’s sanctioned employer unions and - to a large extent - the organised left. When they heard about the occupation, they decided to head over there and contribute to the widening of the struggle.

As Stergios Katsaros, a Guevarist radical who participated in the uprising has explained,

In the construction sector […] there were around 200 to 300 people, former members of Lambrakis youth or EDA (2), now unaffiliated, who always took part in riots […] They were disappointed by the reformism of the leadership of the left, did not participate in any organisation, but were extremely politicised […] There was already a rumour going around that the assemblies from the Law School and ASOEE would decide to end the occupation. These rumours enraged not only the oppositional left but even members of the traditional left. The result was the formation of a small demonstration that headed towards the Polytechnic” (p. 225)

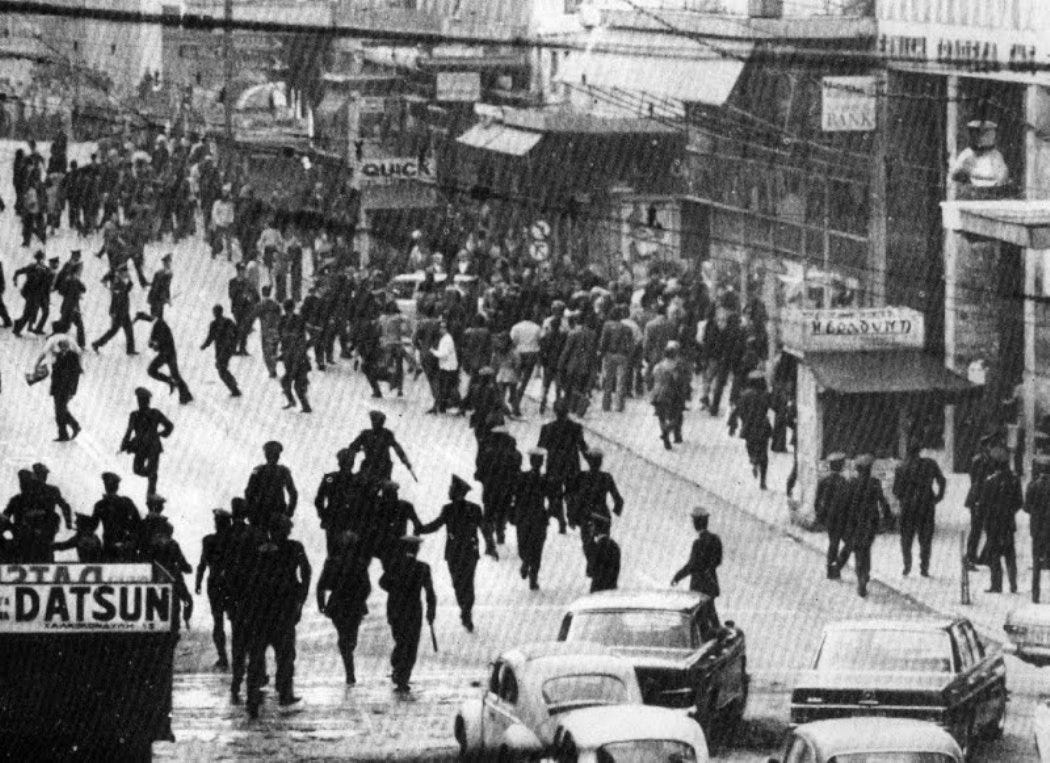

On the morning of November 15th, a large demonstration by construction workers heads towards the Polytechnic.

Meanwhile, the occupation had become a self-organised space that included a medical station, food distribution and a pirate radio created by electrical engineering students and which started broadcasting next to the wavelength of the army’s official radio broadcast. While the range of the pirate radio was very small, its message soon spread all over Greece. “This is the voice of the free students in struggle, of the free Greeks in struggle”.

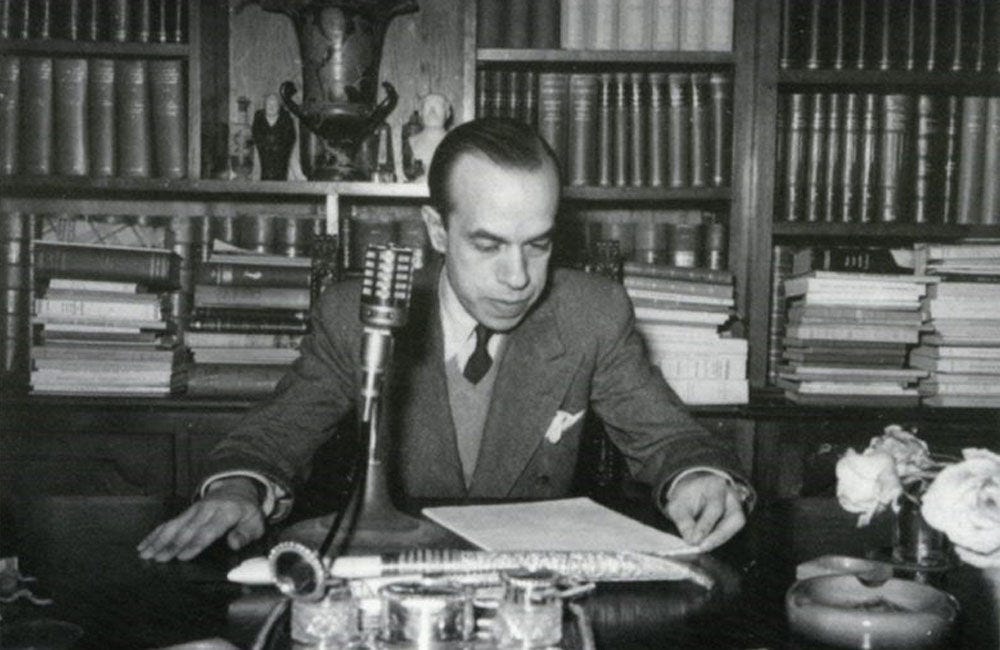

Maria Damanaki and Dimitris Papachristos, the most famous voices of the uprising.

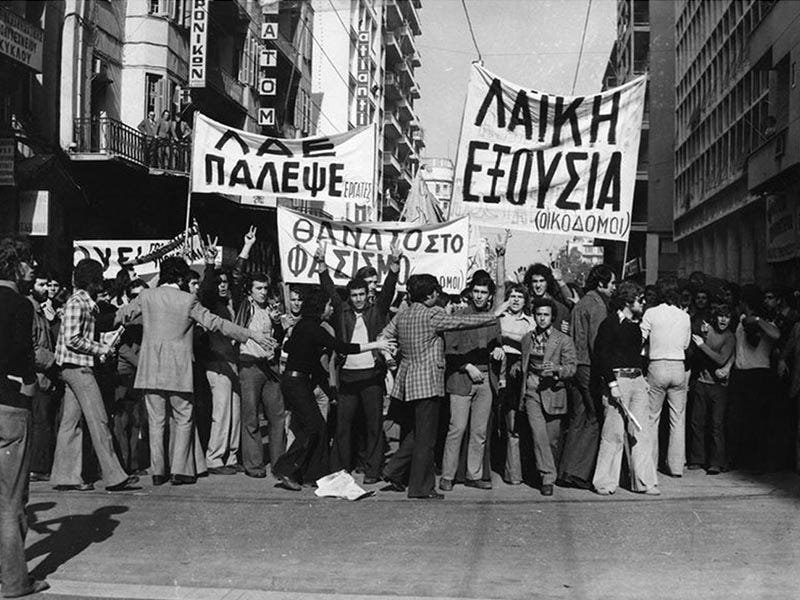

The arrival of workers and the -so far- fruitless attempts by the organised left to de-escalate was soon felt in the streets. Instead of calls for the respect of the openness and democratic process of the student elections, the slogan now was “General strike” and the overthrow of the regime.

“General strike”

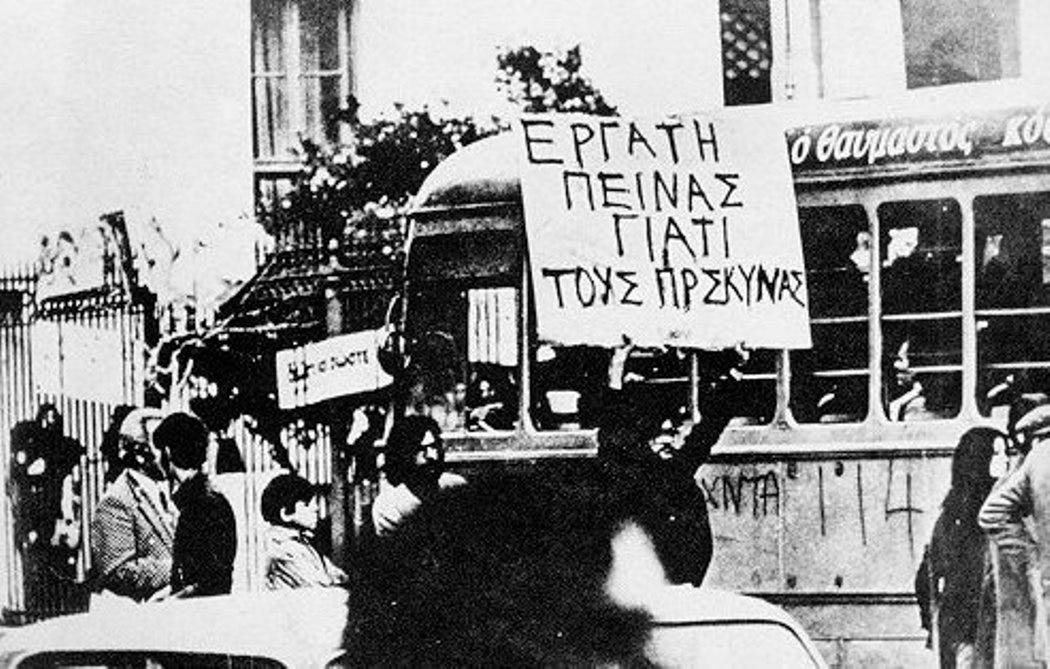

“Worker you are hungry. Why do you obey them?”

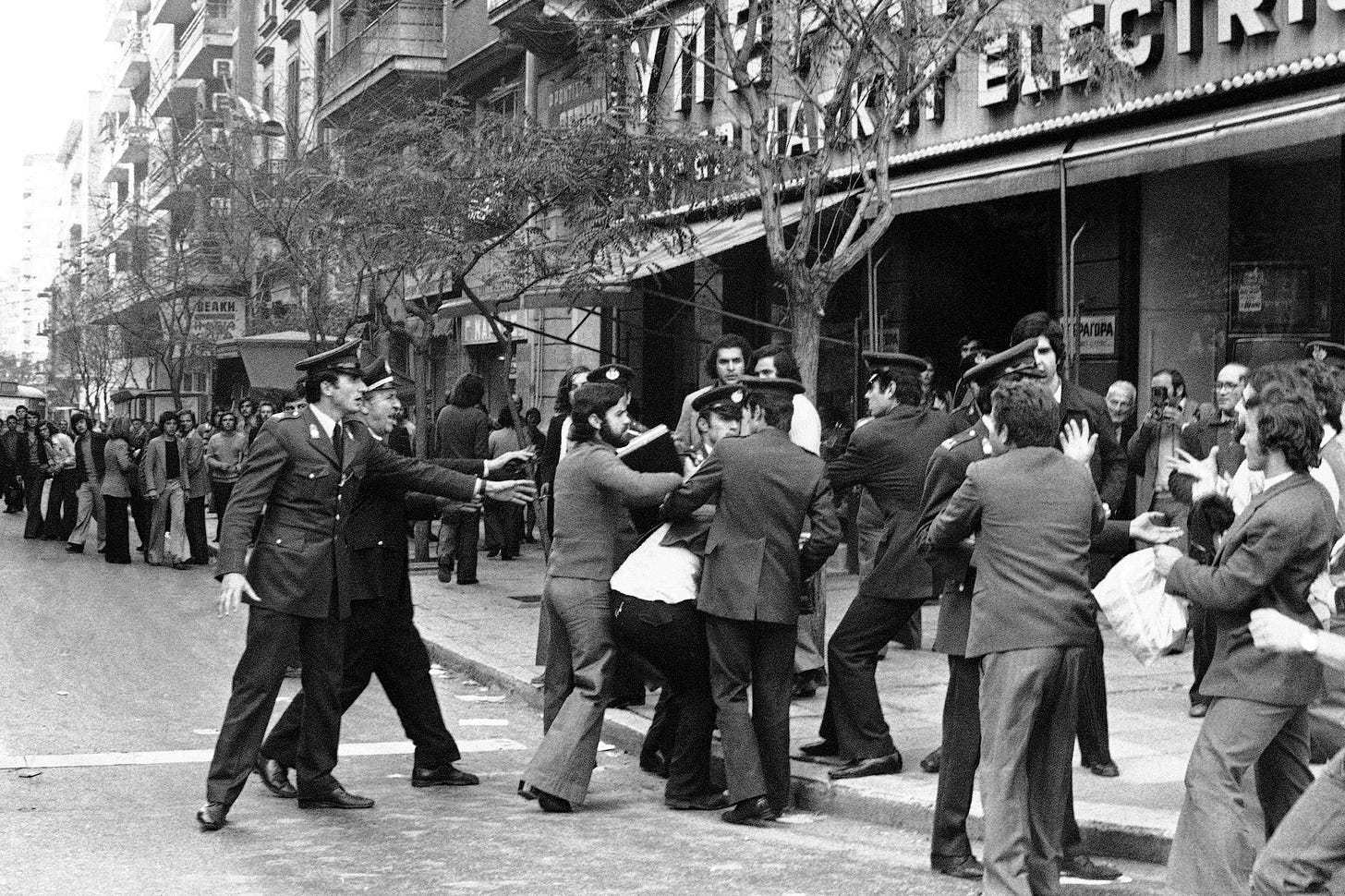

In the surrounding streets, the police would engage in sporadic arrests and attempts to attack approaching demonstrations or individual people. But the dictatorship had decided to let the situation de-escalate and in the afternoon of Thursday 15th of November, the police was ordered to withdraw completely. That meant that the streets were opened and more and more people could join. By midnight, more than 15.000 people were outside the University.

With the composition on the ground changing and a new sense of freedom coming to sweep away 6 years of repression, the joyous atmosphere of the first two days would soon turn into a fierce and violent struggle. But until Thursday afternoon, things remained quiet and celebratory, while the organised left was busy taking gradual control of the occupation committee, the radio and any activities that could pose a threat to their ability to determine the character of the uprising. This meant excluding all non-students from having a meaningful say in the assemblies and the key structures of the occupation.

It was, however, too late. And with few notable exceptions, even those tasked with taking control of the situation and disciplining the increasingly unruly majority were swept away from the passion and radicalism of the moment. The result would become obvious on the next day, Friday the 16th of November.

Notes

(1) The main organisations were that of KNE/Anti-EFEE, the youth organisation of the stalinist communist party (KKE), and RIGAS FERAIOS, associated with the anti-Soviet communist party (KKE ES). KKE ES had split from KKE after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia of 1968.

(2) Lambrakis youth was a left-wing youth movement created after the assassination of EDA MP Grigoris Lambrakis in May 1963. EDA was a legal left-wing political party founded in 1951. While its program was moderate, it remained the main representative of the left inside Greece at a time of the fiercely anti-communist, post-civil war right-wing authoritarianism. Lambrakis, one of its most popular MPs, was assassinated in Thessaloniki by a group of thugs directly employed by the police and following the orders of top government members. The real story of the assassination and the revelation of the conspiracy is the topic of the brilliant film “Z”, by Costa Gavras.

References

Katsaros, Stergios (2008) Εγώ, ο προβοκατορας, ο τρομοκράτης, Εκδόσεις Μαύρη Λιστα

Appendix

Describing the activities of anarchist groups during the uprising, one of the participants, Christos Constantinidis, wrote at a later point:

“Already from Wednesday afternoon this group of (anarchist) comrades used spray paint and, after removing the adverts from the trams that were crossing Patision street, wrote dozens of slogans (as they also did inside the Polytechnic).

The portrayal of these slogans by the state-owned media (television) with the aim of invoking the threat of social subversion led, however, to the opposite result - to the extent that these contributed to a radicalisation and a starting point for overcoming the illusory contrast between democracy and dictatorship. Some of these slogans were:

“Social Revolution”; “State=repression”; “Against capital”; “Down with the state”; “Down with the military”; “May 1968”; “General uprising”; “Against wage labour”; “the proletariat is the gravedigger of wage labour”; “workers’ councils”; “workers have no motherland”; “patriots are assholes”; “Down with authority”.

The panicked response of the lackeys of state and capital to the haughty confirmation of the aims of social revolution was initially crystallised in the illegal “Πανσπουδαστική” (publication of KNE/Anti-EFEE, January-February 1974):

“We condemn the pre-designed invasion into the Polytechnic on Wednesday, November 14th, of approximately 350 organised agents of the secret police, in accordance to the provocative plan of Roufogalis-Karagiannopoulos (note: Roufogalis was a police general and Karagiannopoulos the chief of police), who followed the orders of the now-sidelined dictator Papadopoulos and of the CIA, with the aim of promoting using all thuggish and provocative means ridiculous anarchist slogans and slogans which neither represented the moment or the specific forces (present). They did so in order to isolate our movement and our movement at the Polytechnic from the wider population and the youth. To be able, furthermore, to construct (with the help of the dictatorships media outlets) an image of an isolated extremist revolutionary-anarchist uprising which does not have the support of the people, so that the junta can use it as an excuse for making use of the typical argument of a threatened regime and to justify the reinstatement of martial law and the strengthening of brutal terrorism […]

The plans of Roufogalis, Karagiannopoulos, Papadopoulos and CIA failed miserably. The organised student movement, in its most decisive battle, isolated and crushed the provocateurs. The attack of this motley crew of police agents and pseudo-revolutionaries who, like crows, besiege since years the anti-dictatorial, and especially student, organisations with the aim of corrupting them […] was met with a committed student body that remained steadfast in its consistently decided course.

Therefore, our slogans (“bread, education, freedom”, “20% budget for the education system”, “down with the junta”, “kick the US out”, “Workers, farmers, students”, “All united”, “Popular power”, “National independence”) drowned the pseudo-revolutionary screams of the intelligence service (KYΠ) and its informants who had appeared out of nowhere, had taken over the loud speakers, were shouting slogans such as “Down with the state”, “Down with authority”, “May 1968”, and who had also promoted unrealistic calls for an immediate social revolution and an immediate general strike”.

As for the other side of the organised left, a central figure of KKE ES, Leonidas Kyrkos, would later say in an interview:

In 1973 you had said that the Left should have taken advantage of the openings offered by Spyros Markezinis.

I still believe so. Without Markezinis’ openings there would not have been an uprising and I supported the idea that during the elections, where each citizen would be obliged to confront the dictatorship, there would be an opportunity to mobilise popular support, which was immobile with the Μεταπολίτευση. The μεταπολίτευση happened with the people being absent.

Had you realised how far the Polytechnic uprising had gone and where it was heading?

In the beginning no, but in due course we all realised. We were all against the anarchist slogans and tried to communicate to those inside the Polytechnic that such a direction would be counter-productive. The point was to call for an end of the junta, not an end to capitalism, the state and such nonsense that the anarchists were calling for. In the end our position won the day.