This second instalment deals with the events of Friday the 16th of November, 1973. As mentioned in the previous part, this is the moment when it becomes more than clear that the uprising is no longer focused either on student demands nor controlled by students of the organised left. On this day, thousands of workers, farmers, unemployed, pupils, office clerks and many others join in, each bringing their own characteristics, demands and visions. Friday the 16th is also the day when the junta realises that it has lost control of the situation, as the riots, occupations of public buildings and attacks on police stations spread out way beyond the immediate area of the Polytechnic University.

Friday, November 16th.

Early in the morning, a large delegation of farmers from the nearby town of Megara come to Athens to attend a trial taking place against the business interests of an oil tycoon. These farmers and their families had been engaged in a struggle against an agreement drawn between the junta and the oil entrepreneur which involved the forced expropriation of their lands with the purpose of creating oil refineries. Their struggle had culminated in a general strike on October 12th, 1973, and a massive demonstration of more than 12.000 people on October 14th.

After attending the trial and attempting, fruitlessly, to meet with government officials, the farmers from Megara decide to form a spontaneous demonstration and to head towards the Polytechnic to express their solidarity to the struggle and to ask for their own demands to be added to those already circulating. At around 11.00 in the morning, they reach the gates of a University already filled with thousands of people.

Receiving a warm welcome from everyone, the farmers meet with the student committee and ask for their demands and solidarity to be broadcast on the pirate radio. This happens almost immediately and soon after, the slogan which had characterised their struggle (“This land is ours”) is written on a banner and hung on the gates.

While the academic authorities of the Polytechnic are engaged in their own meetings where they collectively decide not to allow the police to enter the grounds, the junta is also busy trying to assess the situation. In the ministerial meeting, a furious Papadopoulos asks how it is possible that a pirate radio station is broadcasting freely and urging more people to join the uprising. The response he gets is that the station is located inside the Polytechnic and that without a police invasion, it is impossible to stop its transmission. It becomes clear that the only option remaining is to evacuate the Polytechnic.

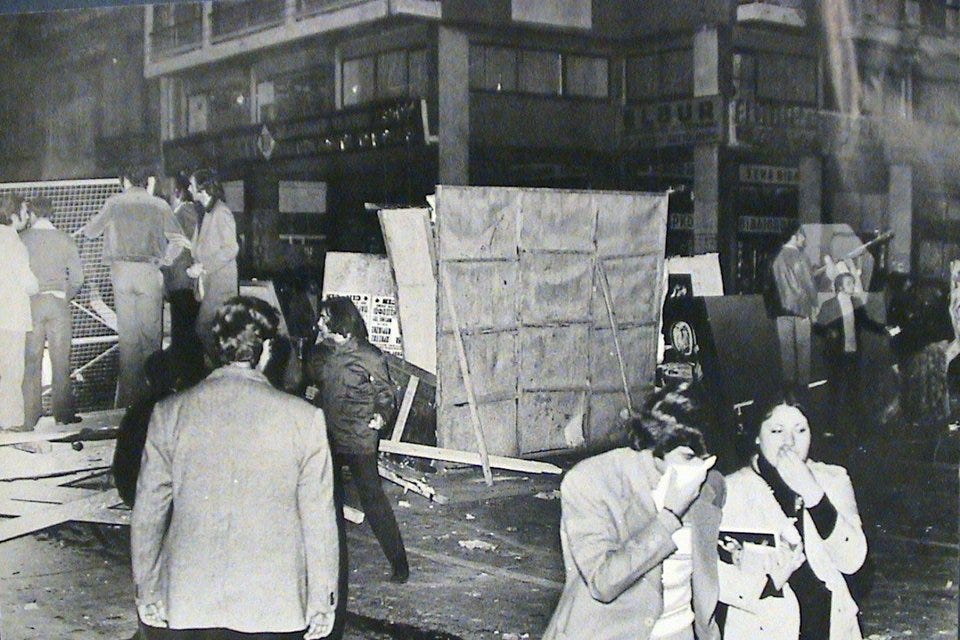

Meanwhile, more people are joining the ranks of the gathered people - workers from the Coca Cola factory, students that had refrained from joining until that moment, an endless flow of young pupils. Dissatisfied with the bureaucratic structure of the student committee inside and in an attempt to spread the struggle beyond the Polytechnic, the spontaneous decision is taken to expand the occupied spaces. Impromptu demonstrations are formed, nearby public buildings are targeted for occupation and police forces are attacked in the streets and their headquarters.

By 18.00 in the evening the riots have escalated. The central building of the Municipality Authority of Attica near Omonoia square has been occupied (we know from testimonies that many of the farmers from Megara ended up there), as have the headquarters of the telecommunications state company. At the same time, large groups of demonstrators target the headquarters of the police located a few blocks away from the Polytechnic, while the Ministry of Public order (a tall building one block away) is sieged.

Around the same time, scattered reports start arriving about the use of live fire by police. We know now that the first shots came from the Ministry of Public Order, a tall corner building situated almost opposite the Polytechnic. The strategy of the police is very specific: while there is a clear view into the open grounds of the Polytechnic, the shots are in fact only aiming at those outside the building and those trying to approach it from different streets. With an eye on stopping people from joining in and keeping the rest isolated into the University, the hope is that the riots will stop and then an order for evacuating the remaining occupiers can be implemented.

The first recorded death is that of the 17 year old pupil Diomidis Komninos, shot through the heart as he was carrying an injured demonstrator back to the makeshift clinic of the University. In total, approximately 24 people will be killed that day and more than 1000 injured. According to testimonies of police officers at the trial for the Polytechnic events that took place after the collapse of the junta in 1974, the police used more than 20.000 bullets in less than 40 hours.

As the violence escalates, so does the number of injured demonstrators. The makeshift medical station in the Polytechnic is quickly overwhelmed and the pirate radio station makes an urgent call to the International Red Cross to send ambulances to collect the gravely wounded, while also begging for surgeons to come to the Polytechnic to assist with on the spot surgeries. Meanwhile, a large group of pupils have created a human chain to facilitate the carrying of the injured. According to testimonies, they kept singing songs all the time to give others and themselves courage.

Faced with this escalation the general secretary of KKE ES Babis Drakopoulos sends a message to the members of Rigas Feraios to abandon the Polytechnic. KKE makes similar attempts. The response from inside is straightforward: it is too late, we are not going anywhere.

Despite the use of weapons, armoured police cars, constant tear gas and attacks by the police (joined by groups of fascists, such as then 16 year old and future chief of the neonazi Golden Dawn, Michaloliakos, who lurk in surrounding streets to beat up isolated demonstrators), people continue arriving in the centre of Athens, forming spontaneous demonstrations and fighting the police in every street corner. By 20.00, such actions have spread all over Athens. State Secretary of the junta Spyros Zournatzis described the situation in a later interview:

Around 18.00-18.30 they attack the first public building […], the Municipality. One hour later, they attack the building of the telecommunications company (OTE). Soon after, they attack the General Headquarters of the Police […] We then heard that there were similar attacks in Zografou [a neighbourhood on another part of Athens]. The situation was completely out of control.

With the police showing clear signs of exhaustion and incapable of stopping the ever growing crowd, the decision is made to call for a military intervention. Between 22.00 and 23.00, students from inside the Polytechnic who are listening in on the police radio frequency overhear the chilling news that military tanks have left the barracks.

In the next 2 to 3 hours fierce debates take place about what to do next. Some want to leave, while small groups are even discussing the potential use of explosives to stop the tanks. Meanwhile, the crowds in the streets have taken their own decision: Alexandras Avenue, the main path taken by the tanks to approach the Polytechnic, are barricaded with the use of cars, buses and cement poles.

Though somewhat delayed by such obstacles, the first tanks arrive near the Polytechnic shortly after midnight and line up across the street. One of them drives and stops right in front of the gate of the University.

Terrified by this turn of events, some students attempt to send a delegation to negotiate with the military authorities. Others are urging them not to use their weapons, trying to appeal to their patriotic feelings. From the wavelengths of the pirate radio station, a desperate Papachristos starts singing the national anthem. It was perhaps hard for these students to realise that it was precisely the soldiers’ sense of patriotism that had brought them there to crush the uprising. A young demonstrator unaffected by such feelings of national pride started crying: “what a terrible end for an uprising”, he shouted. “To die under the sound of the national anthem.” (Katsaros 2008: 243)

It was, by now, the early dawn of November 17th, 1973.