In the early hours of Saturday, November 17th 1973, around 2.30, a last attempt is made to negotiate a peaceful evacuation to avoid further bloodshed. Two members of the student committee exit the University and ask the military authorities for enough time to organise the evacuation, as well as assurances of a safe exit. The army officer in charge responds that the army accepts no deadlines. It sets them. The student delegates are told that they have 10 minutes to evacuate.

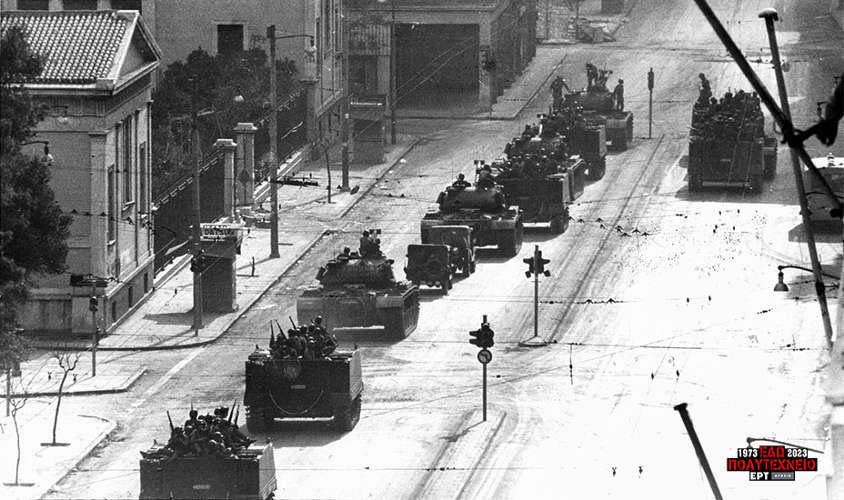

It is still unclear what exactly happened in the next few minutes but most testimonies indicate that upon their return, at least one of the two students tried to open the gate. Those gathered around reacted and tried to stop him. Meanwhile, as a last effort, the Dean’s personal Mercedes Benz which had remained inside the Polytechnic throughout the whole time, was brought behind the gate to form a barricade. While that scuffle is taking place on the gate, the officer on top of the tank decided that the deadline was over. The order was given and the tank, after driving a few meters back, leapt forward in full speed. The gate was crushed. A young man standing on top of the left column of the gate fell to the ground, amidst soldiers of the special forces. A young student’s legs were crushed. It was Saturday, November 17th, 3 in the morning.

The only surviving picture that captures the moment the tank crushed the gate.

Immediately, soldiers and police stormed the University. As the military personnel made its way through the various buildings and open spaces of the university, a group of them reached the makeshift clinic. The doctors and nurses told them that they could not evacuate as there were too many severely injured. Among them Pepi Rigopoulou, whose legs had been crushed by the tank. The soldiers brought a stretcher and took her to the hospital. Eye witness accounts would describe how a few soldiers helped them leave the premises but despite such gestures, the reality was that outside the Polytechnic hoards of enraged police officers were waiting. As soon as the occupiers started leaving, they proceeded to attack, beat and arrest everyone they could get their hands on. According to some accounts, a young man was beaten so badly in those moments that he died of his injuries a few weeks later.

The room were the pirate radio station was held was evacuated at 3.30. The last words broadcast shortly before were an urge to continue the struggle “by any means necessary”.

Those who managed to escape the police ran around in a frenzy trying to escape the police and find a safe passage. Hundreds were sheltered by neighbours in nearby flats. With a few exceptions of some who managed to stay hidden in various parts of the University, by 6 o’clock in the morning the whole area had been cleared.

At 9 in the morning, an official declaration of martial law is signed and broadcast on the radio shortly after (1). The declaration clarifies that all public gatherings of more than 5 people are strictly forbidden, as are any anti-patriotic statements. It also threatens those who are sheltering injured people who are not members of their family with being dragged in front of the emergency military courts that were being set up.

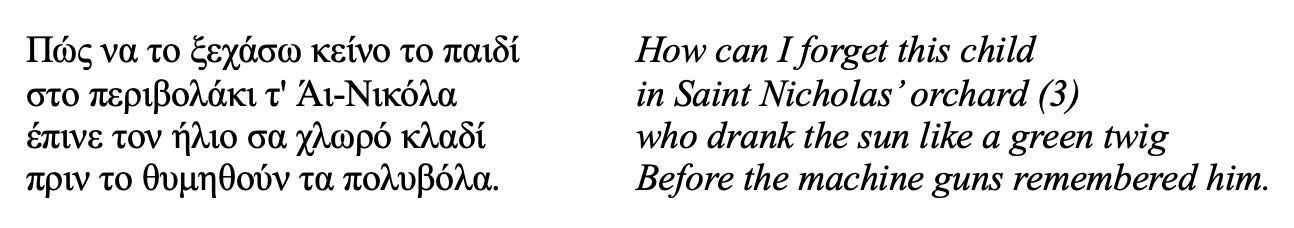

After the declaration is broadcast, military personnel in tanks and armoured vehicles together with police officers roam the streets, weapons in hand. Quite remarkably and despite the martial law and unleashing of this murderous repression, large groups of workers and students continue to congregate in the streets, forming spontaneous demonstrations and attacking police and other public authorities.

Rare footage of the streets of Athens hours after the tanks have evicted the Polytechnic University.

This situation continued until Monday, the 19th of November. According to official records that were made public during the trial a year later, the police also had reports that construction workers were preparing a call for a general strike, while students were also trying to re-group and organise further demonstrations. The general strike never materialised but the same police records note that more than 70 per cent of construction workers in Athens did not show up for work the next days. Those who had not been arrested went into hiding.

These official records, alongside the testimonies of arrestees, witnesses and relatives of the killed and injured, would be collected and published by Ieronimos Likaris in 2023, on the 50th anniversary of the uprising. Apart from the harrowing descriptions of the experiences of relatives and arrested people, along with the evidence of unspeakable cruelty from the police officers, this truly remarkable documentation also allows us to get a better understanding of the social composition of the participants.

For example, two different official records show that of those injured, workers were over-represented by more than 42 per cent (hospital/clinics’ records) or 53 per cent (police records) accordingly. A look at the arrest records for the 17th of November shows a similar pattern: out of 866 arrested on the 17th of November, 475 were workers and 268 were students from technical schools and apprentices. Only 46 were students at the Polytechnic University, while 74 were pupils. The arrest records of November 18th show a similar composition.

While the uprising had been brutally crushed, the political crisis it generated continued to shake the foundations of the junta. Using the events as an expression of the collapse of public order, the fanatic Brigadier General Ioannidis led a second coup that overthrew Papadopoulos and Markezinis, imposing an even harsher dictatorial rule. Among its first decisions was that of re-arresting and sending back to prison and exile many of those who had been amnestied in August 1973. But the days of the junta were, unbeknownst to all, numbered. Following a botched attempt to orchestrate a military coup in Cyprus in July 1974, which was followed by a Turkish military invasion of its northern part, the dictatorship stepped down.

Epilogue

To paraphrase Walter Benjamin, uprisings represent a “leap into the open air of history”. No one can have full awareness of what is happening or exert control over their direction. Small initiatives can determine outcomes without any prior consensus, while attempts to implement pre-existing plans are confronted with a reality that always moves too fast. At the same time, memories of the experiences get reconstructed, a posteriori rationalised and quite often repeated misconceptions get embedded into dominant narratives.

Despite this, it remains a remarkable feature of the narratives that have dominated the Polytechnic uprising ever since that the very same people who admitted their inability to control the events and to impose their own vision continue to be seen as the true representatives of the uprising. It is more than clear in all accounts that if the organised left had had its way, the occupation would have never happened. Or else that it would have ended on the second day. Had they followed the instructions of their political bureaus, their members would have left the Polytechnic on Friday evening. If workers, farmers, unemployed, office clerks and pupils had not taken part, those days would have gone down in history in a notably different way.

But that is not what happened. While the student committee inside the University did its best (and failed) to maintain a modicum of control and while the tightly controlled radio station would only broadcast specific slogans, the uprising was enriched, transformed and radicalised by the thousands who joined in, infusing the revolt with demands, perspectives and a dynamic that no one could have foreseen or prepared. No representative of the political organisations of the left would have willingly acquiesced to the riots, the storming of public buildings or the attacks on police headquarters. Even if some of them had agreed (as surely some did), taken in by a sense of awe at the display of collective strength and struggle, it would not have mattered. The events unfolded despite their presence.

There are very few accounts of those who took part in the initiatives that radicalised the struggle and seriously threatened the tight grip of the junta. It could not be otherwise. A collective uprising cannot be fully reflected in any individual account, no matter how lucid it is. Anyone who has ever experienced such a “leap into the open air of history” knows that its full content remains elusive and contested.

The re-creation attempted here is not different. With the relative benefit of hindsight and an eclectic use of numerous testimonies, it tries however to shed light to events and circumstances that challenge official commemorations that insist on describing what transpired in those days as a ‘student uprising’ or one determined by the decisions and choices of the organised left.

None of the above is meant to imply that the maoist, trotskyist or anarchist groups present had a more decisive political role to play. The intensity of the events cannot be reduced to political ideologies but only, if at all, by the openness shown towards the radical spirit of the moment. It is clear that, as in any other social movement, an explosive mix of political militants and non-militants generated new relations, forms of co-existence and solidarity that both responded to external stimuli and created their own. As is too often the case, the widespread participation of non-militants in such moments brings a directness which, unmediated by ideology, remains more practically inclined. In the right moment, such a perspective facilitates the radicalisation of a struggle, i.e. a focus on the actual root of the social question.

*

The legacy of the uprising at the Polytechnic determined the whole period of the post-dictatorship era (the Μεταπολίτευση). It was (and remains) a contested ground, for the organised left as for everyone else. For decades, for example, marginal fascists would jump at every opportunity to deny the existence of murdered demonstrators. Today, many of them are in government. The official status of the uprising in national history structurally forbids such denialism from becoming dominant. From another perspective, however, the very same official narrative that insists on representing the uprising as student-led call for democratic transition - ignoring its subversive characteristics - has opened the space for a further undermining of the radical elements of the revolt, something visible in various attempts of contemporary representatives of the Right to claim that they also played a role in it. Whether such claims are more or less ridiculous than those who, after the collapse of the dictatorship, belatedly pretended to have been inside the Polytechnic is an open question.

What is certain is that a large part of what Μεταπολίτευση means can be traced back to the 1973 uprising. And in the contemporary environment, μεταπολίτευση has become a cursed word - even, unashamedly, by some of those who took part in these events. Reminiscent of alt-right inconsistencies which castigate some supposed left-wing hegemony, the contemporary Greek Right (aided by the recent incorporation of various fascists) has sworn to “put an end” to all things related to the μεταπολίτευση.

From a certain perspective, one can understand why. One of the most lasting legacies of the Polytechnic uprising is the still-persistent - in significant parts of the population - distrust or even hatred for the police and a certain sympathy towards those who take to the streets. Moreover, for many decades, the fields of popular culture, music, poetry and songs were dominated by depictions and critiques of poverty and exploitation, exaltations of struggles and a consistent culture of remembrance for those who fought and gave their lives hoping to build a better world. While at times admittedly bordering on the banal, the fact remains that the right-wing has not produced anything even remotely capable of capturing and reflecting the emotional strength that flows from such expressions. If the Right has achieved anything, that can be without exaggeration reduced to its remarkable capacity to avoid being held responsible for the tremendous amount of suffering it has caused - from the days of the Nazi occupation until (at least) the end of the 1970s.

For those who - however broadly - identify themselves as part of the left, on the other hand, key events of postwar history continue to be seen as part of a historical continuity. This search for links (or for blurring the distinction between events) is, at the end of the day, inadvertently helped by the simple fact that such suffering and such struggles have been recurring - more often than not in the very same streets.

There is perhaps no better way for demonstrating this than by closing this post with a poem by Nikos Gatsos, whose words and anguish could be referring as much to the events of December 1944 (2) or those of November 17th, 1973. Or both.

Notes

(1) Martial law had been in place from April 1967 until January 1972.

(2) In December 1944, partisans of the left-wing resistance movement against the Nazi occupation supported by the majority of the population, fought (and lost) against the combined strength of newly created army of the minority government, Nazi collaborators and English troops.

(3) Saint Nicholas’ orchard refers to the area of Exarhia, where the Polytechnic University is (still) located.