Theorizing the interregnum

The unfortunate relevance of Fraenkel's Dual State

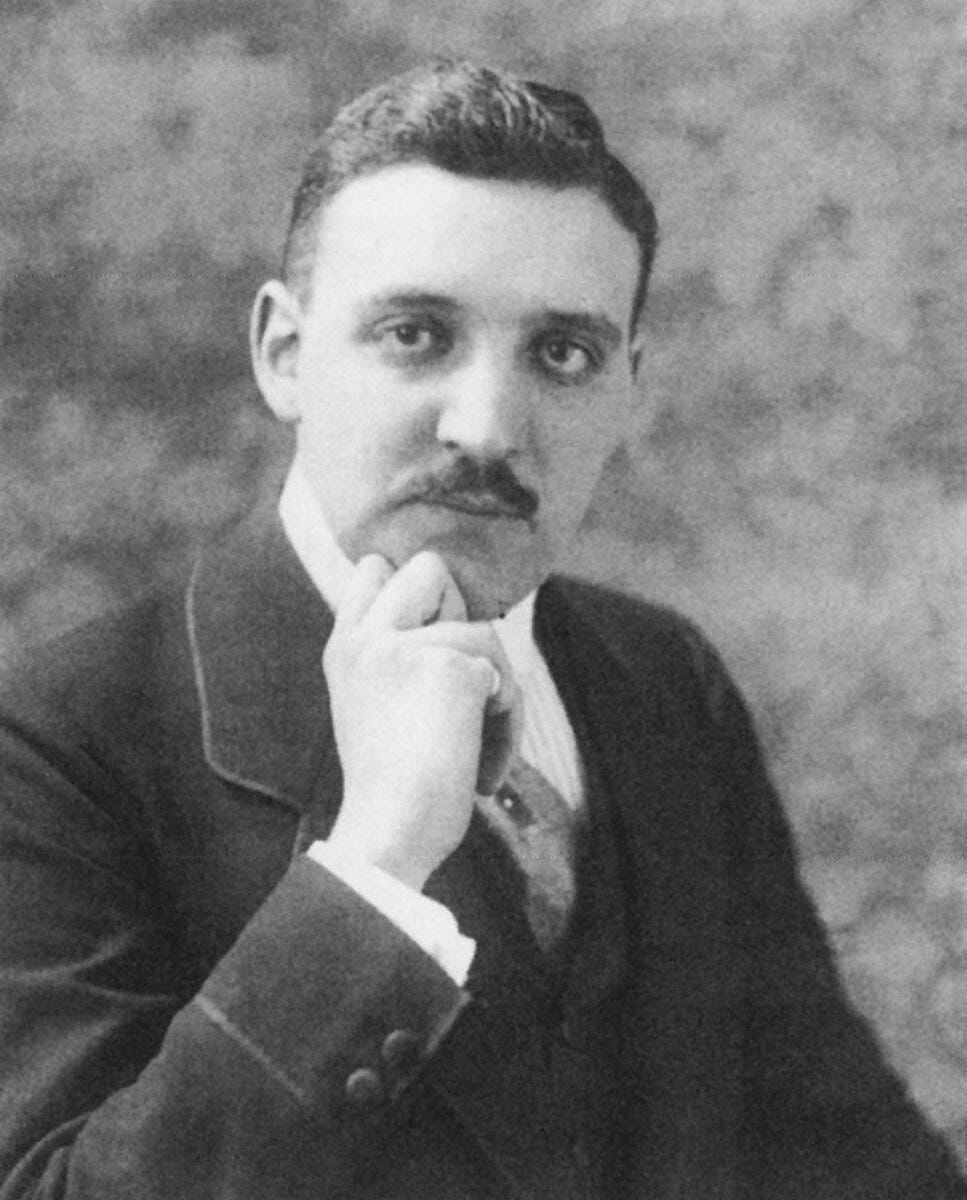

In 1941, Ernst Fraenkel’s book “The Dual State: A Contribution to the Theory of Dictatorship” was published in the US. The author, a German-Jewish labour lawyer, had fled Nazi Germany three years before but the book was written while he was still there, smuggled out in small segments. From a front row seat as a practicing lawyer, Fraenkel was able to observe the gradual transformation of the legal and political system of Germany in its path towards the full dictatorship of the Nazis. It remains quintessential precisely because it is concerned with the interim period between the Nazi invitation to power in 1933 by conservative elites and the dictatorial rule that took shape in the following years. As such, it sheds light into the hybrid character of the transitional moment that created the legal origins of the Nazi dictatorship, refuting attempts which retrospectively describe it as a unitary and coherent structure from its early days. The eventual complete dominance of Nazism did not take place in one swift move but through a series of (often contradictory) processes that created new normals gradually embedded as given. At a time where we also seem to be in an interregnum, his observations have acquired ominous relevance.

Biographical notes: Fraenkel in Weimar

Born in 1898 in the city of Cologne, Fraenkel lost his parents early on and moved to Frankfurt Am Main where he would grow up. After the oubreak of World War I, he enlisted in the army and found himself in the “soul destroying and intellectually sterile” trench warfare. Surviving the war, he went on to study law in Frankfurt under legal giants like Hugo Sinzheimer (one of the authors of the Weimar Constitution), specializing in the fields of sociology of law and labour law. Between 1925 and 1931, he was the chief editor of Die Justiz, where he authored many articles against legal positivism. At the same time, and following Sinzheimer, he became a Marxist social-democrat and penned many pieces for Die Tat and the SPD’s newspaper Vorwärts, as well as interventions on labour law in the Arbeitsrecht journal. In 1926 he became the legal advisor of the German Metalworkers Union (IG Metall), opening a private practice office next to the headquarters of the union in Alte Jakobsstrasse together with Franz Neumann.

[Tempelhofer Ufer 16A, Berlin, where Fraenkel’s first private practice office was situated]

During the Weimar Republic, Fraenkel remained in constant dialogue with legal figures like Sinzheimer, Neumann and others further developing his criticism of legal positivism. But he was also committed to the “struggle for the emancipation of the proletariat” (Fraenkel 1926). As Ruth Dukes explains in her brilliant The Labour Constitution (2014), this meant that Fraenkel positioned his approach to law in conjunction with the activities of the labour movement. As she wrote, for Fraenkel

the development of labour law was contingent on the labour movement enjoying a significant measure of political strength. Until the point in time when the movement was stronger politically than it was socially and economically, it was likely to rely on its industrial might to force concessions from employers. Only when industrially weak and, at the same time, represented in Parliament, would labour leaders think to utilize law as a tool for the advancement of their interests.

Dukes 2014: 12

For Fraenkel and Sinzheimer, the emergence of labour law as a distinct discipline during the Weimar Republic marked the positive disentanglement of labour relations from private law, under which formally legal contracts between individual workers and employers masked the mute compulsion inherent in the fundamentally unequal relation between economically strong employers and weak, atomized workers. Collective bargaining, as opposed to individual contracts, contributes to the autonomous creation of norms, rendering economic relations a public rather than private matter.

This was a key framework for the creation of an economic constitution (1) [Wirtschaftsverfassung] within Weimar’s constitutional order, a concept that ranged from institutionalising the collective strength of labour all the way to structuring legally labour’s participation in economic decision-making.

In substance, the economic constitution referred to the various laws that allowed for the participation of labout, together with other economic actors, in the regulation of the economy: not only terms and conditions of employment, but also production - what should be produced and how.

Dukes 2014: 13

Such a vision for the economic constitution did not come to pass during Weimar’s turbulent period, partly because of internal opposition within the SPD for expanding workers’ participation and control over the economic process. This position was born out of the fear expressed by trade unions and employers’ associations about the rising power of the revolutionary workers’ councils, which the SPD willingly conceded with the Works Councils Act of 1920 (which ignored Sinzheimer’s proposal for the creation of workplace, district and national workers’ councils and opted merely for workplace structures) and the violent repression of workers’ protests against it (2).

While initially Sinzheimer would argue that the management of the economy should be clearly separated from the state, allowing economic actors to enforce the economic constitution autonomously, he nonetheless did not support an unmitigated freedom for economic actors. Equal participation in framing interests did not exclude stronger influence on the very same process by specific actors. For that reason, the state should be granted the role of general arbitrer of the ‘public good’, a role in which the state could (and should, according to Sinzheimer) act decisively to prevent “industrial action [which] threatened the public interest”, as well as “[protecting] individuals from harm at the hands of powerful economic actors” (Dukes 2014: 25).

Rejecting Sinzheimer’s conceptualization of the state as a “unitary entity separate from society embodying the common interest” (Ibid: 27), his student Kahn-Freund would locae the principal flaw of the Weimar Republic in the granting of too much power to the state, thereby annuling the autonomy of workers. Asigning this role to the state meant that the ‘public good’ became identified as the consequence of an almost corporatist collaboration employers and workers mediated by the state. This ‘social ideal’, as he called it, transformed labour law from “an instrument to assist the rise of the suppressed class [into] an instrument of the state to suppress class contradictions” (Ibid: 26).

Fraenkel would also criticise the process of abandoning the vision included in the economic constitution. Writing in 1929, he would argue that

If one compares Article 165 with the social and political realities, one must draw the conclusion that the construction of the economic constitution was not only not completed - since 1920, it has not even been seriously contemplated. When one reads in Article 165 that district works councils and a national workers council should be responsible for the achievement of socializing legislation, that workers should participate on a parity basis in the regulation not only of wages and working conditions but the entire economic development of the productive forces, one must smile a weeary smile.

Fraenkel, Kollective Demokratie, 1929: 86, cited in Dukes, p. 22

On a similar tone, he would also reject the use of Art. 48 - which allowed for rule via emergency decree through bypassing parliament - calling the specific constitutional sections “Diktaturparagraphen”.

* *

The repression of the radical workers’ movement by the SPD and the Catholic Zentrum was accompanied by a balancing act between providing positive reforms for workers (in terms of working conditions and welfare expansion) and a strategy of appeasement for private capital. From a monetary perspective, this was supported by monetary financing through a central bank which was, however, exclusively concerned with protecting its gold reserves and indifferent to the effects of money printing. This strategy culminated dramatically after the French army’s invasion of the Ruhr area when a state-proposed general strike saw the relentless printing of money to support both the workers’ strike against the occupation and capital’s losses - leading to the outbreak of hyperinflation in 1923.

Soon after, a new monetary approach initiated through a currency reform and the termination of monetary financing by new Reichsbank president, Hjalmar Schacht, led to a relative stabilization of the economy, opening the way for capital inflow in the form of (primarily short-term) loans from the US. The concomitant relaxation of the reparations requirements through the 1924 Dawes Plan brought forward a new predicament: the loans provided by the US were utilized to make reparations’ payments towards the European victors of World War I, who would use them in turn to settle their own debts to the US. This recycling mechanism functioned relatively smoothly - until, that is, the 1929 crash which abruptly cut credit outflows from the US and plunged the world (and Germany) into the Great Depression.

By mid-1929, however, even before the European markets and banks had felt the most dramatic consequences of the Depression, SPD had lost its parliamentary majority and a Zentrum government with Heinrich Brüning at its head embarked into a radical austerity process centred around balancing the budget, correcting deficits and reversing as many as possible of the concessions given to workers. By that time, the structure of labour/capital relations and their mediation by the state had followed Sinzheimer’s logic - but not its content. For the state was not the social-democratic state that Sinzheimer had envisioned, nor was the economy socialized or democratized. In the absence of such a transformation, the interpretation of the ‘public good’ that the state was meant to uphold was once again identified with the interests of private capital. Having dispensed with politically-motivated strike activity (dealt with through the use of military/para-military forces), other forms of industrial action seen as ‘threatening the peace’ could also be cut short. In this context, legislation such as the Arbitration Decree of 1923 (which allowed the state to resolve industrial disputes through compulsion) was now exclusively used to cut wages (Dukes 2014: 40).

Unemployment figures shot through the roof and engended a form of economic instability whose consequences, however, were almost exclusively concentrated on the working class and the poor. This is the moment when the so-far largely irrelevant nazi constituency starts its ascend towards power, leading eventually to Hitler’s January 1933 appointment as Chancellor by a cohort of conservative elites led by Marshal von Hindenburg.

Fraenkel and Nazism

In the early months of Nazi rule, Fraenkel belonged to those who believed that this was an untenable, temporary parenthesis that would soon collapse under its own contradictions and irrationality. By March 1933, however, it was becoming obvious tat this was a grave miscalculation. In that month only, Hitler granted amnesty to those convicted of crimes “for the good of the Reich during the Weimar Republic” (such as the Nazi murderers of Polish communist Konrad Pietzuch in the village of Potempa), he outlawed political parties and trade unions (among which IG Metall) and issued a Verttretungsverbot against Jewish legal practitioners (3). The house arrest of Sinzheimer in the same month and that of Franz Neumann’s two monthls later shattered any illusions left. While Neumann took the opportunity of his release to flee the country, Faenkel stayed in Germany and tried to fight from within. His official rejection of the Verttretungsverbot as legally void did little to help him but he eventually benefitted from the intervention of von Hindenburg who pleaded (and achieved) the exemption from prohibition for those Jewish lawyers who had fought in World War I (like Fraenkel), those who had begun their practice before 1914 or those who had lost a family member during the war. To the disdainful surprise of Nazis, this ended up representing almost 60 per cent of Jewish lawyers, allowing more than 1700 of them to continue their practice.

It goes without saying that this temporary permission was far from the end of the story. In what can be seen as a first expression of what Fraenkel would later call the dual state, the Nazi association of laywers (Bund NS Deutscher Juristen) immediately reacted to the exemption by mobilising Nazi and SA assault squads to storm the courts, chase down and beat Jewish lawyers and judges. In Kassel, the lawyer Max Plaut was dragged into a former SA hangout tavern which had been transformed into a torture chamber and beaten to death.

[Dr. Max Plaut, *1. Juni 1888; † 31. März 1933, Kassel]

The Dual State

Even though the exclusion of Jews from economic and social life was not fully completed until 1938, those who did not leave the country, end up in a concentration camp or dead, would be subjected to increasing economic deprivation and isolation. Despite the complete absence of any institutional support and with minimal means, however, Fraenkel continued to practice law, focusing (primarily but not exclusively) on the defence of those charged with political crimes and persecuted by the Nazis. Without mounting political defences when defending his clients to avoid exposition, he did however use his legal skills to represent them in ways that even won him several acquittals. At the same time, he also psedunymously authored pamphlets which attacked the Nazi regime in an attempt to unite socialist resistance circles. In one of those, he wrote:

Yes, we have become criminals. If we were not empowered by our illegal activity, I fear that we too would sink into the smog that oppresses Germany. Because we work illegaly, we keep ourselves fresh. That is the point of illegal socialist work in the Third Reich. To infuse the workers with strength, the waverers with trust, the sufferers with hope and the rulers with fear.

While his file was revisited by the Nazis in 1934, this time for “communist activity”, Fraenkel managed to escape the worst and continue his legal practice and resistance activities until his own escape from Germany in 1938 , six weeks before the Kristallnacht. It was in the period between 1933 and 1938 that Fraenkel took frantic notes of the events and transformations that were taking place at both the legal and political level - notes that would form the basis for his Dual State. And it is precisely his observations in this interim period that make his work invaluable - not as an anatomy of the Nazi dictatorship as is generally known but as a systematic recording of the gradual transition from the fragile Weimar democracy to Nazi terror. He observed and theorised, in other words, the interregnum. As he wrote in the 1974 German edition of the Dual State,

[The book] was written in an atmosphere of lawlessness and terror. It was based on sources I collected in National Socialist Berlin, and on impressions that were forced upon me day in, day out […] They stem mostly, though not exclusively, from my work as a practicing lawyer in Berlin in the years 1933-1938 […] The ambivalence of my bourgeois existence caused me to be particularly attuned to the contradictoriness of the Hitler regime […] Anyone who did not shut his or her eyes to the reality of the hitler dictatorship’s administrative and judicial practices, must have been affected by the frivolous cynicism with which the state and the party called into question, for entire spheres of life, the validity of the legal order while, at the same time, applying, with bureaucratic exactness, exactly the same legal provisions in situations that were said to be different.

Fraenkel 1974: xviii, cited in Fraenkel 2017: xlviii-xliv

One of the things that Fraenkel noticed in those early years was that many practictioners within the judicial system were still able to use legal means to help those persecuted by the Nazis - often in seemingly unconventional ways. For example, he observed that

it was common, even for defense attorneys, to push for lengthy prison sentences in order to spare clients the terror of the Nazi concentration camps to where they would likely have been sent in the event of an acquittal or lesser sentence. Fraenkel [also] acknowledged the collusion of ‘humane judges’ who for the same reason imposed lengthy prison sentences on defendants who stood to otherwise fall into the hands of the prerogative state.

Meierhenrich 2017: xxxvi

Such initial anecdotes formed an underlying skeleton for Fraenkel to develop his theory of the dual state, a concept that first appeared in one of his pamphlets published in 1937 (Das Dritte Reich als Doppelstaat). At an initial stage, Fraenkel noted that a German historical legacy that saw a concepual and practical separation between the state as a political unity (Staat als politische Einheit) and the state as a technical apparatus (Staat als technischer Apparat) was being morphed, under the Nazi regime, into a form of governance in which political and technical aspects co-existed. This did not mean that they were equalised (there was a clear primacy of the political state) but their co-existence indicated something quite unique about this transitional phase.

If the technical features of the state were historically characterised by the predominance of “legal norms, rules, codes, and procedures” (Meierhenrich 2017: xlii), the political aspects of the Nazi transition from authoritarianism to totalitarianism were characterised by an apparent lack of a system, of a clearly identifiable strategy or fully-elaborate planning. In fact, he noted, the legal provisions that Nazi authoritarianism was pushing forward and structuring its operations were

without exception so shallow in substantive terms that they amount to no more than the appearance of a legal norm (Ibid)

Nonetheless, the validity and continuity of previous legal norms was not abolished but rendered contingent on its compatibility with political priorities. The transitory character of this process, however, could still be interpreted as pointing towards two different directions: towards the complete subordination of the technical to the political or towards a ‘return to normality’ - which can also explain why many saw Nazism as a temporary parenthesis.

Fraenkel would eventually formulate this dualism through his conceptualization of the co-existence of a normative and a prerogative state. As he noted, crucial elements of the normative state of affairs remained visible (and, in fact, operational) even while they potentially contradicted the prerogative aspects of Nazi rule. For Franekel, understanding this uneasy co-existence became essential for gaining clarity about the authoritarian transformation that was taking place.

To begin with, Nazi proclamations of hostility towards the previous regime in all its aspects was a persistent theme that both fuelled their self-image and made any continuity seem impossible. In fact, the speed and determination with which executive directives were issued in the first months was so overwhelming that it became difficult (even for the Nazis themselves) to keep a grip on the changes taking place. But Fraenkel soon realised that an abrupt break with the normative state would in fact be counter-productive in relation to objectives that were compatible with both the normative and prerogative sides.

In what can be seen as early drafts of the book, one of them consisted of the necessity of maintaining the capitalist order. As he wrote in Das Dritte Reich als Doppelstaat,

If capitalism wants to remain capitalism, it requires at home a state apparatus that recognizes the rules of formal rationality, for without a predictability of opportunities, without legal certainty, capitalist planning is impossible. Capitalism today demands of the state a double: […] first, the formally rational order of a technically intect state […] furthermore, a state that provides the political supports necessary to ensure its continued existence.

Frankel 1937, cited in Fraenkel 2017: xliv

In the context of Germany in the late 1930s, this meant to

recover from the disastrous recession, to accumulate capital and to engage in high-pressure development of certain key technologies: the technologies necessary to achieve the regime’s twin objectives of increased self-sufficiency (autarcy) and rearmament.

Tooze 2006: 114

While never abandoning the connection between the capitalist order and Nazism, Fraenkel tried to ensure in later versions that his presentation did not suffer from the reductionism that characterised orthodox marxist approches. Seeing the capitalist order and Nazism as mutually constitutive, he would argue against the notion that nazism was merely a product of capitalism, pointing instead at the way it was “capitalized”. Bringing this insight into the examination of the legal structure of the Nazi regime, he would write that

the legal order of the Third Reich is thoroughly rationalized in a functional sense with reference to the regulation of production and exchange in accordance with capitalistic methods. But late capitalistic economic activity is not substantially rational. For this reason it has had recourse to political methods, while giving to these methods the contentlessness [sic] of irrational activity.

Fraenkel 2017: lv

As Meierheinrich notes (Fraenkel 2017: lix), the publication of the book in the US forced Fraenkel to tone down even further the (still) marxist approach to the relationship between capitalism and Nazism, visible in the change of phrases such as “the economic structure of the dual state” into “the economic policy of the dual state”. But he always maintained that the “institution of private property in general and of private ownership in the means of production [was] upheld by National-Socialists both in principle and in fact […] even for businesses towards which the National-Socialist program had shown some degree of antipathy.” (Fraenkel 1941: 172-3). And while specific rights that emanate from private property were reconfigured (in the form of controls over investment, foreign trade, capital export, prices and consumption), “income from private property is now, on the whole, much safer than it was before” (ibid).

The central argument of his book (and its continued relevance today) remains the sophisticated exposition of the concurrent existence of the normative and prerogative aspects of the state, despite their at times conflicting imperatives and friction. This particular institutional design explains, according to Fraenkel, the peculiar co-existence of an arbitrariness alongside appeals to order which, when viewed individually, confused commentators into prioritising one side at the expense of the other.

For Fraenkel, the institutionalisation of a lack of boundaries (to the degree of apparent lawlessness) that appears as the essence of the prerogative side of the state is concomitant with the persistence of normative elements that guarantee predictability of legal contracts of economic activity. Similarly, the disregard (or even proclamations of abolition) of constitutional restraints and judicial review exist side-by-side with long-term considerations.

Fraenkel insisted that this hybrid form of governance included transgressive, restrictive and constitutive elements: transgressive in the form of undermining normative expectations but also restrictive towards the prerogative state - in the sense of maintaining a capacity for long-term planning along established economic relations. Finally, the dual state was also constitutive of an emerging new normality that would allow the prerogative elements to “rub off” on the operation of normative legal institutions.

Fraenkel’s final particularly pertinent observation consists of his elaboration of the consequences of this institutional design. Here, after observing that the perseverence of normative elements came with a degree of discretion for those engaged in legal practice, he also took note of a peculiar development. Caught between the transgressive and constitutive sides, judges and other state officials still acting within the remnants of the normative state would actually use that very discretion to expand the logic of the prerogative state. In expectation of the forthcoming new normality, Fraenkel noted, judges would impose self-restrictions (to judicial review, for example) and act in self-binding ways that instrumentalized their discretion in the service of further dismantling the normative state. In this way, the remaining normative elements became, in their hands, the driving force for pushing the transition towards the full dominance of the prerogative state.

* *

Fraenkel’s analysis remains significant because, above all, it demonstrates a particular logic of authoritarianism that does not rely on the discovery of direct and/or conrete historical parallels and similarities. Rather, it offers a sophisticated engagement with the contradictory elements of an authoritarian transformation and their interplay. It is clear that if one seeks to compare our transitional period with the 1930s, a forbidding degree of disparity will (should) immediately throw obstacles to such an approach. There are no Hitlers, SS or SA troops confronting a growing radical workers’ movement with a specific vision that questioned the fundamentals of the capitalist social order. Nor are contemporary developments emerging in the aftermath of an unprecedented massacre that radically challenged the foundations of a Belle epoque. But if one is interested in gaining some clarity about the logic underpinning authoritarian rule and the potential consequences of a politicisation that follows the Schmittian ‘friend-enemy’ distinction that reduces politics to the pursuit of existential enemies, Fraenkel’s Dual State remains - unfortunately - indispensable.

Notes

(1) The concept of the economic constitution would be appropriated by the German neoliberals shortly after. In contrast to Sinzheimer’s conceptualization centered around the promotion of economic democracy, neoliberals saw the economic constitution as the necessary legal framework for the facilitation of the market economy, structured and maintained by a strong state capable of insulating democratic interference. If Sinzheimer’s understanding of the economic constitution rested on the creation of a “legal framework which served at once to limit the power of the sovereign/employer to govern/manage and to guarantee the right of the citizen/worker to participate in the exercise of power” (Dukes 2014: 31), the neoliberal vision of the economic constitution was one of a legal framework created and protected by a strong state meant to limit both the ability of employers (private capital) to act in ways which distorted market competition - by forming cartels, for example - and to obstruct any potential for workers to not only exercise but even influence the exercise of power.

(2) In January 1920, a workers’ demonstration against the Works Council Act was attacked by the police, resulting in the death of 42 people and the injuring of 105. Three months later, workers would nonetheless heed the call of the government to go on strike against the Kapp Putsch, playing an active role in defeating the reactionary coup attempt. While the leaders of the attempted coup suffered no consequences for their open disregard towards the democratic government, receiving a full amnesty in August 1920, the workers who went on strike to defeat them were met with brutal repression, with hundreds of them executed, often by soldiers who had actively participated in the coup itself.

(3) The Verbot was also meant to apply to Communists but, as Jarusch notes, they were difficult “to define in legal practice. As a nationalist bureaucrat, Reich Minister of Justice Franz Gürtner maintained that ‘an attorney’s representation of Communist interests in the course of his professional duty should not in itself justify the assumption of ‘Communist activity’’ (Jarusch 1990: 129). It was only gradually that positions such as those of Prussian State Secretary Roland Freisler, a fanatical Nazi who maintained that “the voluntary defense of Communists in political case is to be seen as Communist activity in principle” (Ibid), would become the dominant interpretation.

References

Dukes, Ruth (2014) The Labour Constitution: The Enduring Idea of Labour Law, Oxford Monographs on Labour Law

Fraenkel, Ernst (2017) The Dual State: A Contribution to the Theory of Dictatorship, Oxford University Press

Jarausch, Konrad H (1990) The Unfree Professions: German Lawyers, Teachers and Engineers 1900-1950

Meierheinrich, Jens (2017) Introduction to The Dual State, Oxford University Press

Tooze, Adam (2006) The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, Penguin Book