Who are you?

And where were you?

[Katja Lang, The Forest]

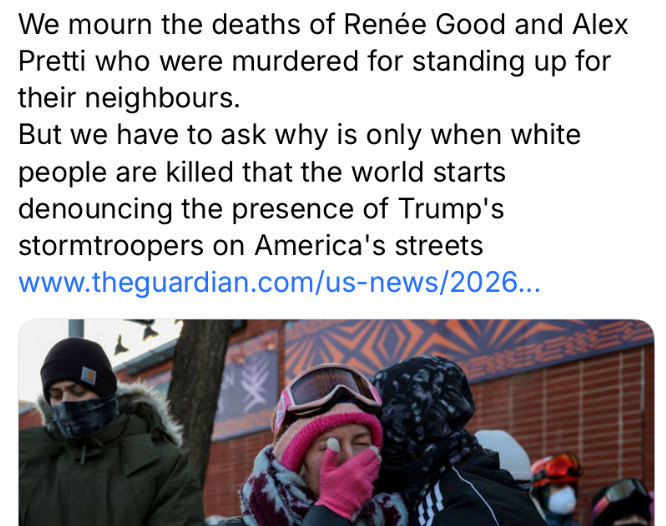

Scrolling through this void called the internet, I came across the following post on social media. Let me however start with a clear disclaimer and explain that I do not know the group that posted this - which is why I didn’t include their name. I want to simply use this quote as indicative of a wider perspective that I have seen circulating for a long time beyond the US and which I have also seen repeated all too often in the last days during the events in Minnesota. Rather than a critique of the specific group, I want to make some comments about the perspective - and its resonance beyond Minnesota. But I also admit that I chose the specific example because its language encapsulates quite well a particular view that I have long found very problematic - in the US or elsewhere.

Let me start by noting that the quote in the picture addresses/accuses “the world”. I have never really understood what people mean when they use such empty signifiers - especially ones that readers can interpret by filling the gap with whatever they have in mind. Who exactly is “the world” that is being lamented for its belated denunciation?

Does “the world” mean the mainstream press? In this particular case, this could be a plausible explanation, given the Guardian example pasted just below. But if that is the case, why not say ‘the mainstream press’?

Since it is hardly news that the mainstream press is not on the side of those who rise up against the state, I find it more likely that “the world” is meant to include all those who apparently denounced ICE only after the murders of Renee Good and Alex Pretti.

More importantly, the rhetorical question answers itself: the obvious reason for the “delay” in denouncing ICE and its stormtroopers lies in the fact that its latest victims were white. That, we are meant to infer, is the reason “the world” is denouncing ICE now and, obviously, why it was not denouncing them before. “The world”, apparently, did not care about non-white victims of ICE. The latecomers denouncing ICE today are not simply latecomers but are, in fact, racist.

I want to avoid focusing on the self-righteous attitude on display (‘the world’ as opposed to ‘us’), as well as the social media-fuelled explanatory toolbox which seems to animate so much of today’s activist left.

I would rather focus on the direct implications of such a perspective and what it shows about one’s understanding of (as well as failure to understand) social movements and mobilisations.

* * *

To begin with, it is rather bizarre to read that “the world” did not denounce ICE before the murders of Good and Pettri. Even from afar, one could hardly miss the mobilisations (and sometimes riots) against ICE in Chicago, LA, NY etc. Reading between the lines, it was even more obvious that these mobilisations and protests relied (there, as everywhere else) on a lot of ground work and anger by neighbours, activists, communities.

It was also rather clear that Minnesota’s protests were larger than before but already here we reach a first critical observation: since when does it make sense to react to the widening of a movement … by accusing those who joined it at a later point?

Social movements and large protests never start as such. They develop, engage more people, strengthen themselves, multiply. This is the definition of a social movement. More than that, all historical evidence shows - and anyone who has taken part in social movements also knows - that the straw that breaks the camel’s back is always … a straw. Not an anvil.

This is crucial because it allows one to get a better grasp of how social movements work. It is hardly ever the case that the excuse or the ‘event’ which causes people to rise up in massive numbers is something much ‘worse’ than what had happened until that moment. Outbreaks of social antagonism are not linear, cumulative processes where one humiliation and affront is superseded by a worse humiliation and affront until ... “enough is enough”.

Writing about rebellions in the distant year of 1951, Albert Camus had already observed that the final trigger which unleashes a rebellion is never an event worse than those which preceded it. People do not revolt because the latest attack/event crossed some imaginary line. What brings (and keeps) people to the streets, what makes them willing to stand up against state forces despite abuse, danger and repression is not some individual decision, a type of “I’ve had enough”. Rather, it is a form of indignation against everything that has led to that moment, that last straw, which, very crucially, finally finds collective expression.

One sees a lot of interviews where individuals are asked to explain what brought them to the streets but it is impossible (and in fact quite problematic) to try and make sense of social movements through the filter of individual opinions. Each single individual who appears at a protest can and will, when asked as an individual, answer such a question differently and will be unable, obviously, to explain all the reasons behind their presence.

Overcoming the fear of facing a powerful and violent state machine alone by getting a sense of collective strength and possibility is the key for bringing people to the streets. Not individual indignation. Individual indignation, in fact, is that which allows people to write angry rants on social media, not what brings them to the streets. It is a glimpse of collective power and the unfolding of an often unpredictable social dynamic that gives each individual the opportunity to … stop being an individual.

* * *

The perspective visible in the original quote from the picture above actually reflects a rather strange attitude of lamenting the … widening and even strengthening of a movement by rather abstractly questioning and doubting people’s motives for joining (and for not having joined previously).

For this precise reason, it reminded me of the squares occupations in Greece back in 2011, when ‘seasoned’ activists displayed the exact same behaviour and peculiar mistrust against such a widening.

But some context is perhaps necessary.

* * *

In May 2011 Greece was in its second year of harsh austerity measures. Starting in April 2010, the restructuring process had been met with some strikes, demonstrations and riots which mostly consisted of the ‘usual suspects’, namely politically active workers and unionists, left wing parties and groups, anarchists. In all, a rather limited number of people - especially compared with what was to follow.

The tragic death of 3 bank workers after a fire broke out during the riots of the largest demonstration to date (May 5th 2010) had also somehow ‘frozen’ the social landscape and the antagonism against austerity.

More crucially, however, a majority in Greece had experienced the first year of austerity cloaked in the illusion that it did not affect them personally. Given that the main thrust of the restructuring process was aimed at reducing state expenses, many felt that if you were not a public employee you were in the clear.

It took about a year for that same majority to come to the realisation that austerity affected everyone. That slashing public expenditures directly affects general consumption, money circulation, employment. And it also took a while for a large part of the population to realise that pre-existing social/political mediations (personal relations with politicians or political parties, official trade unions, mass media) were not only incapable of protecting their clienteles but were actively supporting austerity.

As this realisation was growing, a call was made to assemble at Syntagma square to protest and show indignation. The spectacle of a similar type of protest in Spain had played a role in this but the actual situation on the ground one year after austerity had began was more important.

In any case, at the time no one knew who had made the call - it had initially circulated online, a novelty in the Greek landscape, and only later had it started appearing in posters around the city walls. Nonetheless, when the day came, more than 30.000 people showed up.

Given the origin of the call, as well as the lack of clarity or exact aim of the protest (it was neither a strike nor a demonstration) the turn out was both impressive and indicative of something new.

Nonetheless, one of the first things I remember upon arriving there on that day was a friend and comrade exclaiming “this is awful”, adding “what a bunch of a-political Facebook idiots” etc. Another one put it in even more direct terms: “where were they when XYZ happened?”.

The message was clear. “They”, this a-political bunch of latecomers whom ‘we’ have never seen before, are not a movement and they definitely do not belong in ‘our’ movement.

The implications were also clear: instead of rejoicing at the expansion of social antagonism and the widening of a movement to include those who had not taken part before, the chosen attitude was to criticise them for their previous absence. (1)

In Greece of 2011, the previous ‘absence’ of those who had taken the streets and occupied Syntagma and other squares was not obviously seen as indicative of some structural racist bias - as in the original quote from Minnesota. They were rather being attacked for being a-political, for not caring enough (before), for not being in synch with ‘our’ perspective and ‘our’ militancy which had brought us to the streets so much earlier and so many times before.

It was, however, equally indicative of a self-righteous activist pat in the back and an excuse for scorning those who had not ‘been there’. At the same time, it was reflective of an attitude which, at the end of the day and whether one sees it or not, does not wish to see social movements emerging. It is an activist perspective which sits comfortably and happily within its bubble, with its marginalisation an inverse reflection of its more advanced understanding of the world and of what needs to be done.

That was the clear case of Greece in 2011. In Minnesota, however, given the relative absence of constant social pressure and social movements in the US, a similar perspective gains the extra characteristic of accusing those who take to the streets belatedly of actually harbouring problematic political positions, i.e. racism.

* * *

It is hard to understand how those who endorse such a view can possibly know in advance that the people who took to the streets in Minnesota had not denounced ICE during its invasion of Chicago, LA etc. Is also hard to understand why someone would assume that these people were not also in the streets during the George Floyd uprising or any other mobilisation that has happened ever since. Finally, I also find it difficult to fully grasp the role and significance of (online) ‘denunciation’ in contemporary politics and why it has ended up being more important than actual presence in the streets.

In any case, these remarks are of a general nature and, as explained, not aimed at the particular group which published the quote used. More importantly, none of this is meant to imply that there is something inherently positive in social mobilisations or that there is any reason to glorify them simply because they are indications of social antagonism.

Protest and social antagonism can take many different and contradictory forms, it can have reactionary elements and it is very often the case that people enter protests with a whole series of illusions, problematic opinions or motives. The main argument of this intervention is that the only way to overcome such contradictions, illusions about the way forward and a myriad of different individual perspectives is to be part of a collective movement and to embrace its widening. Patting oneself in the back for “already holding the right position”, speculating about why people had not risen before (without recognising the importance of the gradual realisation of collective strength) and criticising those who “arrived late” is not.

———————-

Notes

(1) When the squares’ movement grew even larger, occupying Syntagma square and spreading to other cities for almost two full months, some of the previously sceptical activists changed their attitude and joined the protests. Even then, however, it was clear that some of them had joined in order to “show people how it is done”, i.e. still retaining a distant and vanguardist perspective. Quite often, this led to comic-tragic situations because from the perspective of some ’seasoned’ activists, “showing the way” meant convincing the ‘apolitical’ crowd to endorse their suggestions as they emerged from their comfort zones - even when they were entirely and visibly pointless. A specific example can clarify this: during an almost 10.000 strong assembly discussion in Syntagma on how the square should respond to a new set of austerity measures meant to be passed by parliament the next day, most activists fought tooth and nail to have their proposal accepted, i.e. to organise a typical demonstration with a typical route, starting quite far away from the square and leading up to it. For some ‘apolitical’ people, this made no sense. Instead of a demonstration starting far away from parliament and ending up there, they suggested blockading parliament from really early in the morning, stopping any MP from setting foot inside and voting.

If one thinks they already hold the right position they'll never need to face the difficulty of keeping social movements together and tackling hard questions about the best course of action. I even wonder sometimes if they'd manage to if everyone just magically agreed with their position.

Great post, Pavlos! It really got me to think about activist rhetoric/attitudes.